On August 17, 1774, the front page of the local weekly Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet featured a startling and powerful essay by Caesar Sarter, a formerly-enslaved African man who lived in Newburyport. The timing was significant. The Boston Tea Party had happened just eight months before, and white colonists, already on the path to revolution, were writing impassioned pamphlets and treatises about throwing off the yoke of British oppression. In the midst of that revolutionary ferment, Sarter’s essay pointed out the hypocrisy inherent in their talk of liberty, as long as colonists continued to enslave people. “I need not point out the absurdity of your exertions for liberty while you have slaves in your houses.”

Who was he?

Caesar Sarter’s essay mentioned only a few personal details, and that’s all we know for sure about his life, because sadly no other writings by or about him have surfaced. He was born free in Africa. In his youth, he was “trapanned,” i.e. entrapped into slavery, and brought against his will to this land. He was enslaved for over 20 years, and somehow gained his freedom. Sarter wrote cryptically of his bondage that “at last, by the blessing of God,” he had “shaken it off.” He mentioned having eleven other relatives still enslaved, but provided no specifics.

We can infer some additional details of Sarter’s life. He was obviously intelligent and well-read, familiar with the rhetorical strategies that would frame a strong argument. He was Christian, and well-versed in the Bible and the Calvinistic theology confessed in New England churches. He probably was born in West Africa, the destination of most slave ships at that time. His enslaver’s name was most likely “Sarter,” although there are no records of nearby families by that name, only a few near-matches with wealthy ship captains named “Carter” and “Salter.” Perhaps “Sarter” was a pseudonym. Or Sarter had been enslaved far away, and came to Newburyport after gaining his freedom, leaving enslaved family members behind. Newburyport was a thriving ship-building and shipping town in the 1770s, and Sarter may have found work in one of the skilled trades in high demand. Too little is known of this thoughtful and eloquent man.

The essay

Caesar Sarter pointedly addressed his essay “To those who are Advocates for holding the Africans in Slavery.” His essay came across like a sermon, warning that God would judge harshly the actions of colonists who would seek their own “liberty” from British oppression without first granting liberty to the people they were enslaving.

Sarter opened by referencing the popular talk of “natural rights and privileges of freeborn men,” and sharing that, “from experience,” he agreed that liberty was preferable to slavery, and he could understand why the colonists’ forefathers came to this land given the tyranny they’d felt in England. But then he asked his readers why, since they drew such a distinction between the evils of slavery and the blessings of liberty, they didn’t equally pity the Africans they enslaved.

He further built his argument by referencing the Biblical injunction to “Do unto others, as you would, that they should do to you.” Sarter asked his readers to imagine being torn “the husband from the dear wife of his bosom…or parents from their tender and beloved offspring,” or else the horror of having “your wife and children, parents and brethren, manacled by your side.” And after surviving that harrowing journey, the indignity of being exposed to sale “as though you were a brute” and being flogged for crying at the prospect of permanent separation from your loved ones. Sarter challenged his readers: “Are you willing all this should befall you?”

Sarter quoted specific Bible verses to support his point, for example Exodus 20:16, “And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.” He referenced the Christian teachings that his former enslavers had introduced to him, and asked his proslavery readers to apply them to slaveholding.

Caesar Sarter was aware of certain proslavery justifications that colonists had put forth, such as that Africans were better off enslaved in this land than free in their own land, which they claimed was “ignorant.” Sarter offered two rebuttals. First, his “ignorant” or perhaps “innocent” homeland in Africa had not taught evil through “vicious examples,” as slaveholders in the colonies had done. And second, “every man is the best judge of his own happiness, and every heart best knows its own bitterness.” In other words, don’t tell me what’s best for me; I can judge that for myself, thank you.

Sarter wrapped up with a recommendation, that if the colonists wanted freedom they should begin with Step 1, namely liberating the oppressed Africans among them. “Then, and not til then, may you with confidence and consistency of conduct, look to Heaven for a blessing on your endeavors to knock the shackles with which your task masters are hampering you.” In other words, don’t expect God to support your struggle for freedom from the British if you refuse to grant freedom to your slaves.

About the printers

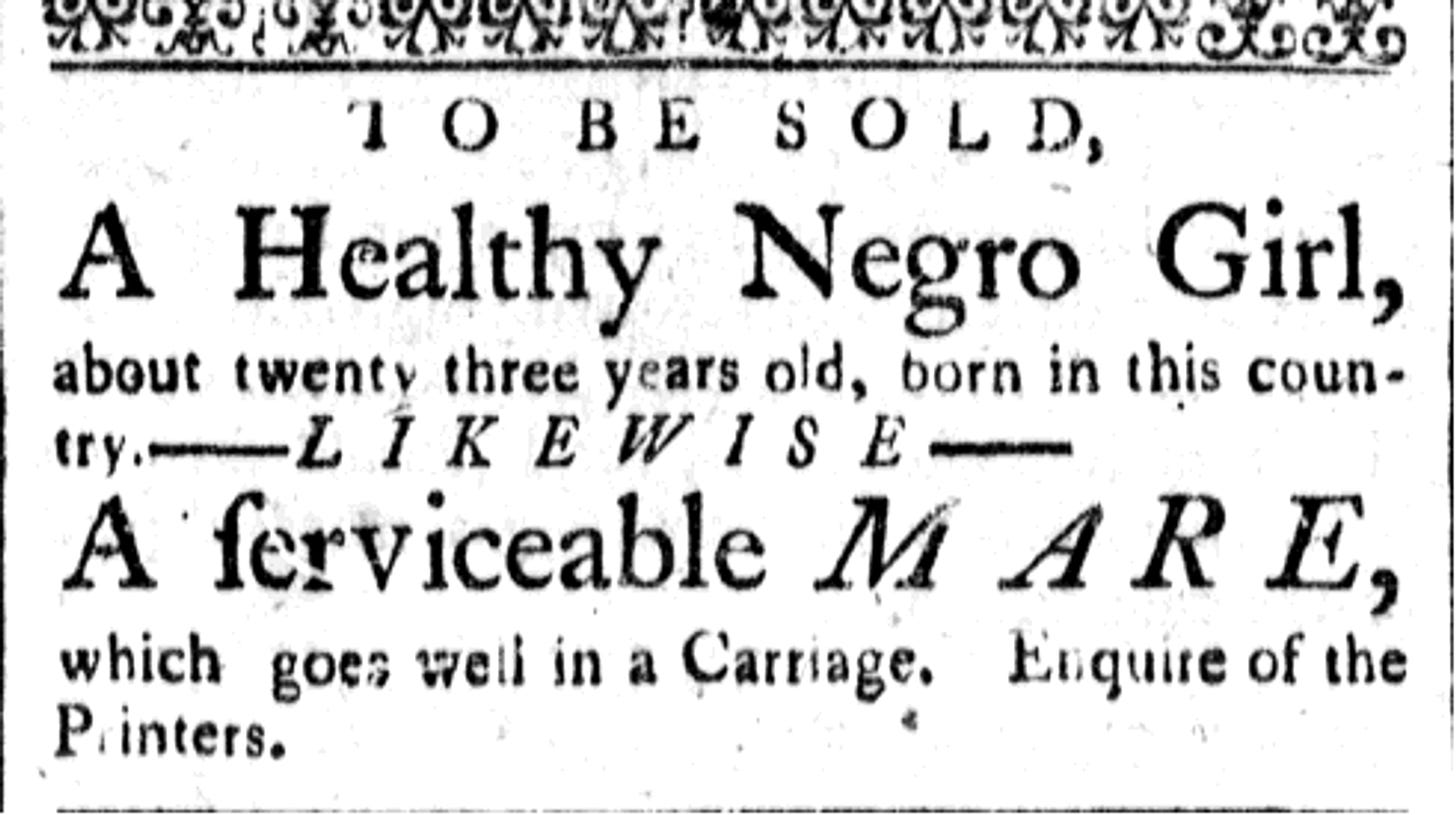

It’s not only startling that a formerly-enslaved African man submitted this bold piece for publication, but also that the Essex Journal published it. Newburyport shipbuilders and merchants who presumably read the paper benefitted from the slave trade, the paper was not considered radical, and the era of antislavery newspapers such as The Liberator began decades in the future. The Essex Journal was even known to publish occasional ads from slaveholders seeking to buy or sell, such as this ad from earlier that year.

One possible clue: the Essex Journal had experienced a change in ownership. Isaiah Thomas of Boston had been the publisher, but the back page of the same August 17 issue announced that the paper was now under new management. Isaiah Thomas had sold the printing equipment to Ezra Lunt, a Newburyport business man who ran the stagecoach to Boston. Henry W. Tinges continued as the printer.

The essay’s impact

In those days, local papers from nearby towns would often reprint articles of broad interest. But when I searched the newspaper archives for mentions of Caesar Sarter, I found only the one essay published on August 17, 1774 in the Essex Journal. Sarter’s essay was not picked up by other papers, nor did he have other writings published under that name.

Sarter’s essay certainly was unusual for the time. Perhaps it hit too close to the bone. Perhaps readers preferred the comfort of their own righteous indignation.

We don’t know how the people of Essex County received Sarter’s essay in 1774. But the paper circulated in Newburyport and surrounding towns, and may have been passed around. The free and enslaved Black population would no doubt have taken interest, and discussed the essay among themselves.

Caesar Sarter’s name is not found in many histories of the antislavery movement. His audacious words appeared in 1774, and then they disappeared. But Caesar Sarter deserves to be known, as a bold and intelligent African man who endured slavery and dared to challenge — in print — the white colonists who held slaves while complaining of being treated like slaves by the British.

Selected references

Bell, J. L. 2018. “Newburyport Newspapers.” Boston 1775 blog. https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2018/03/newburyport-newspapers.html

Caesar Sarter, “Address, To Those who are Advocates for Holding the Africans in Slavery,” The Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet (Newburyport, MA), August 17, 1774, 1. Digitized and available online through the Newburyport Public Library. http://newburyport.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?i=f&by=1774&bdd=1770&bm=8&bd=17&d=08171774-08171774&fn=essex_journal_and_merrimack_packet_usa_massachusetts_newburyport_17740817_english_1&df=1&dt=4&cid=2710

Cameron, Christopher. 2011. “The Puritan Origins of Black Abolitionism in Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 39 (1 & 2), Summer 2011. https://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Puritan-Origins-of-Black-Abolitionism.pdf

Cameron, Christopher. 2014. To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement. 41-44. Kent State University Press, 2014.

City of Newburyport. 2023. “Grant Us our Liberty.” One-page graphic about the antislavery efforts of Caesar Carter and other Black residents of Newburyport: https://www.cityofnewburyport.com/sites/g/files/vyhlif12211/f/uploads/7._newburyport_blackhistory_panel7_230823_final_ol_preview.pdf

Davis, Thomas J. “Emancipation Rhetoric, Natural Rights, and Revolutionary New England: A Note on Four Black Petitions in Massachusetts, 1773-1777.” The New England Quarterly 62, no. 2 (1989): 248–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/366422.

Nash, Gary. 1990. Race and Revolution. Contains the full text of Caesar Sarter’s essay on pages 167-169. https://archive.org/details/racerevolution0000nash/page/166/mode/2up

National Park Service. African Americans in Essex County - list of towns and resources https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/upload/African_Americans_EssexCo_FINAL.pdf

Sesay Jr., Chernoh M. 2014. “The Revolutionary Black Roots of Slavery's Abolition in Massachusetts.” The New England Quarterly Vol. 87, No. 1 (March 2014), pp. 99-131 https://www.jstor.org/stable/43285055