Exactly 182 years ago, on November 17, 1842, a Black man who’d fled slavery in Virginia stepped out of a Boston jail and became a free man. But the law did not free him; the people did.

For a few months in 1842-1843, George Washington Latimer was the 23-year-old poster child of the Massachusetts antislavery movement, and his name was on everyone’s lips. But for the rest of his life, Latimer was an ordinary working man, just making his way in the challenging conditions that formerly-enslaved men faced in the 19th century.

In this piece, I’ll tell George Latimer’s life story, as far as I can from the limited records about his life before and after the antislavery movement rallied around him. In Part One I’ll tell of his early life in slavery, his escape, his capture in Boston, and the outrage that grew around his case.

It’s an Essex County story, partly. Latimer spent much of his life in freedom as a paperhanger in Lynn, and he’s reportedly buried there in Pine Grove Cemetery, in an unmarked grave. Also, for an intense six months, antislavery people of all stripes in Essex County and across Massachusetts focused their energies on the Latimer Case, and helped to pass the “Latimer Law” in 1843, which banned the use of Massachusetts state resources in capturing or re-enslaving people who had fled slavery.

Early life

George Washington Latimer was born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia in 1819. His mother Margaret Olmstead was enslaved by a white stone mason named Edward Latimer, who worked in the Norfolk Navy Yard. George’s father was Edward’s half-brother Samuel Mitchell Latimer, who worked with him in the Navy Yard. George was very light-skinned — an attribute that became relevant later when he fled enslavement.

George was apparently the only enslaved child who Edward kept. In the 1820 census, Edward’s household included 16 enslaved people, only one of whom (I presume George) was under the age of 14, which suggests that Edward sold the other children born to the five young women who he enslaved.

George spent his childhood as a domestic servant in Edward Latimer’s household, and remained there after Edward died and his widow remarried a man named Mallory. As was typical for enslaved children, George wasn’t taught to read or write.

The Latimers and Mallorys and other families who bought and sold George Latimer and exploited his labor were not wealthy plantation owners. They were city people of average means, who lived alongside free Black families in Norfolk. When George was 16, Mallory began hiring him out to various tradesmen. In this common arrangement, George was fed and housed by the tradesman for months at a time, doing whatever work was demanded, earning a little money for himself, and handing over some of his earnings to Mallory. In this way, George spent his young adulthood enslaved as a laborer, dray driver, horse tender, coal measurer, and store clerk. But he was also able to save up a little bit of cash.

The tradesmen — some of them free Black men — treated George harshly, with frequent beatings and slim rations. Later, after George arrived in Boston, he described the physical abuse he’d endured in slavery as something to be expected. For example, he said one tradesman’s wife “was very disagreeable. She struck me once over the head with a shovel, because she claimed that I was slow in getting some water. She frequently would make her husband beat me with a stick. Otherwise, I fared very well.”

George was also jailed twice, for weeks at a time, for unpaid debts — incurred not by him, but by his enslaver Mallory. George’s narrative glossed over his unwarranted imprisonment and the floggings he received there, and summed up his experience in jail as “Got on very well, except for food.”

It’s impossible to read George Latimer’s matter-of-fact description of his enslaved life without grieving not only that he suffered such treatment, but that he grew up believing the abusive treatment was normal.

In October 1839 a bill of sale conveyed George Latimer to the last of several enslavers, a Norfolk storekeeper named James B. Gray, who George claimed “made all his money by selling liquor to colored people.” George tried to get away in 1840, but didn’t even make it to Baltimore before being overtaken, and returning to face even harsher treatment from Gray.

In February 1842, George married a woman named Rebecca Smith, who was enslaved by Mary D. Sayer. After their marriage, George would often spend the night with his wife and return before sunrise to Gray’s storehouse on Wide Water Street, receiving extra beatings when Gray thought he was late.

By October 1842, George and Rebecca had one more reason to try to get away. Rebecca was expecting their first child; she was six months pregnant.

Self-emancipation

On October 4th George and Rebecca hid themselves in a boat in Norfolk harbor and didn’t emerge until the boat had reached Frenchtown, Maryland — a spot at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay, well past the busy slave markets of Washington DC. From there the two traveled to Philadelphia, with light-skinned George posing as a white gentleman and Rebecca as his servant. George used their savings to purchase a first-class cabin, so the two of them could hide in plain sight. Once they reached Philadelphia they were in the free states. And from there to Boston, as George described, “it being a presumably free country, we travelled as man and wife.”

Meanwhile, in Virginia their two enslavers published adjacent ads in the Norfolk paper, seeking the Latimers’ return and promising a $50 reward for each of them.

Most enslaved people who fled the South were single men. To escape as a husband and a pregnant wife was riskier, and more daring than most people would even attempt. But George and Rebecca Latimer, determined to build a life in freedom for themselves and the child they were expecting, successfully reached Boston on October 7th or 8th, despite the long odds.

But on arrival in Boston, George and Rebecca didn’t even get a moment to celebrate. They immediately encountered a white man from Norfolk, who recognized George and sent word to James B. Gray.

Assisted in Boston…and arrested in Boston

By 1842 the free Black community in Boston had built a robust mutual aid network, which connected new neighbors with housing and work, cared for orphans and widows, expanded education for Black children, and assisted people who’d fled bondage in the South, like the Latimers. George and Rebecca Latimer quickly connected with this community; they were said to be housed by “friendly blacks.”

On receiving word of the Latimers’ presence in Boston, James B. Gray immediately travelled north, intent on dragging George back to Virginia. Rebecca’s enslaver didn’t follow, perhaps expecting that Gray would succeed and Rebecca would have to return with her husband.

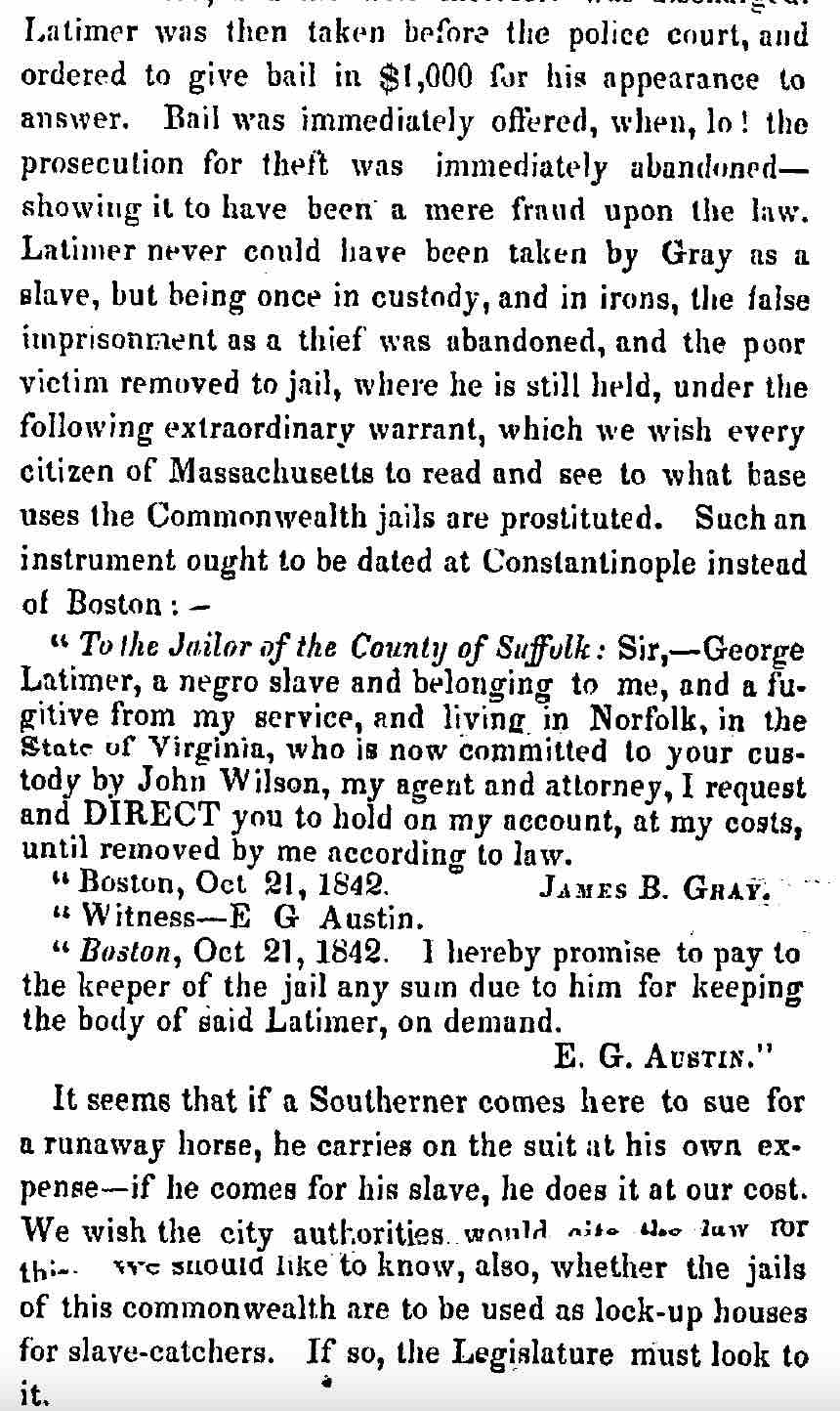

In Boston James B. Gray hired a local attorney, and they convinced a Boston judge to have Latimer arrested on false charges of larceny. With these false charges, Gray could compel Boston authorities to detain Latimer; if the only charge against Latimer was escaping slavery then Gray himself would have been responsible for finding and capturing Latimer.

On the day of the arrest, the Boston Black community turned out in force to protest. Hundreds gathered at the courthouse on October 20th, and then followed the Boston police officers transporting Latimer to the Leverett Street jail, which was located in Boston’s West End, just west of today’s North Station.

The protesters made their outrage conspicuous. They probably hoped to rescue Latimer as well, as they had in other fugitive cases in recent years. But Boston police that day not only jailed Latimer; they also arrested several Black protesters for disturbing the peace.

After the Boston authorities had successfully detained Latimer, Gray then dropped the false larceny charge and claimed that Latimer should instead be held in jail as a fugitive from slavery. The Massachusetts judge agreed to this maneuver, and gave Gray two weeks to produce evidence that George Latimer was his enslaved property, later extending that to a month. Bostonians were furious that in this way the federal government could make state and local authorities complicit in Southern slavery.

Support for the Latimers

The Boston Black community could not prevent George Latimer’s arrest. But the community jumped into action on behalf of the Latimers. Rebecca Latimer was safely hidden in the home of a friendly abolitionist. And for several evenings after Latimer’s arrest, Boston’s top Black leaders met at the Belknap Street church, also known as the African Meeting House. Led by Black Baptist minister Rev. John T. Raymond and Black abolitionists Charles Lenox Remond and William Cooper Nell, their meetings set in motion a multi-prong effort.

One committee of Black Bostonians approached former president John Quincy Adams, to ask him to assist white abolitionist attorney Samuel E. Sewall in defending Latimer. (Adams was a known ally; he’d supported antislavery petitioning efforts, and recently represented the African men in the Amistad case that went to all the way to the Supreme Court, but he declined.) Another committee collected funds to cover Latimer’s legal expenses, and to fund “the protection of other fugitives.” Also, a clergy outreach committee approached the various Boston churches, asking them to pray for the Latimers and collect funds for George’s defense.

The Latimer legal case

The sad truth is that James B. Gray had federal law on his side. Our nation’s founders had word-smithed the Constitution to guarantee the rights of enslavers, while shrewdly avoiding the words “slave” and “slavery”:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

— Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U. S. Constitution signed in 1787

To strengthen this clause, in 1793 President George Washington signed into law an act that again cleverly avoided the term “slave,” but established that an enslaver or their agent could enter a free state, seize a person they claimed as their property, convince a local judge (not a jury) of their claim, and transport the person back to slavery. The law also penalized anyone who would hinder the process.

But by 1842 the Boston Black community had become more organized, and white Bostonians’ support for slavery had weakened somewhat, so Boston antislavery people could at least make the climate hostile to Gray and his agents to pursue his case in Massachusetts. Meanwhile, Latimer’s legal defense team could press on tensions between federal and state or local jurisdiction.

For example, did state or local authorities actually have to help an enslaver arrest supposed enslaved people? The federal government operated no jails in Massachusetts at the time, so where would they keep someone like George Latimer? Who would pay the cost of jailing him? Could an out-of-state person hire a Boston police official to detain someone like Latimer? Did Latimer have the right to have his identity and status determined by a jury? What evidence would Gray have to provide as proof that Latimer was legally enslaved by him in Virginia? How much time would Gray be granted to produce that evidence? Would the governor of Virginia need to send an affadavit in order to remove Latimer from Massachusetts? Would the Boston bar association allow Massachusetts lawyers to represent the interests of Southern enslavers in Massachusetts courts?

For several weeks, Latimer’s defense team challenged Latimer’s detention. The Boston Black community raised funds for George’s defense and took care of his pregnant wife Rebecca, who was nearing her due date. White abolitionists published a dedicated paper called The Latimer Journal and North Star three times a week, providing up-to-date news on the Latimer case. All of Boston was glued to the news.

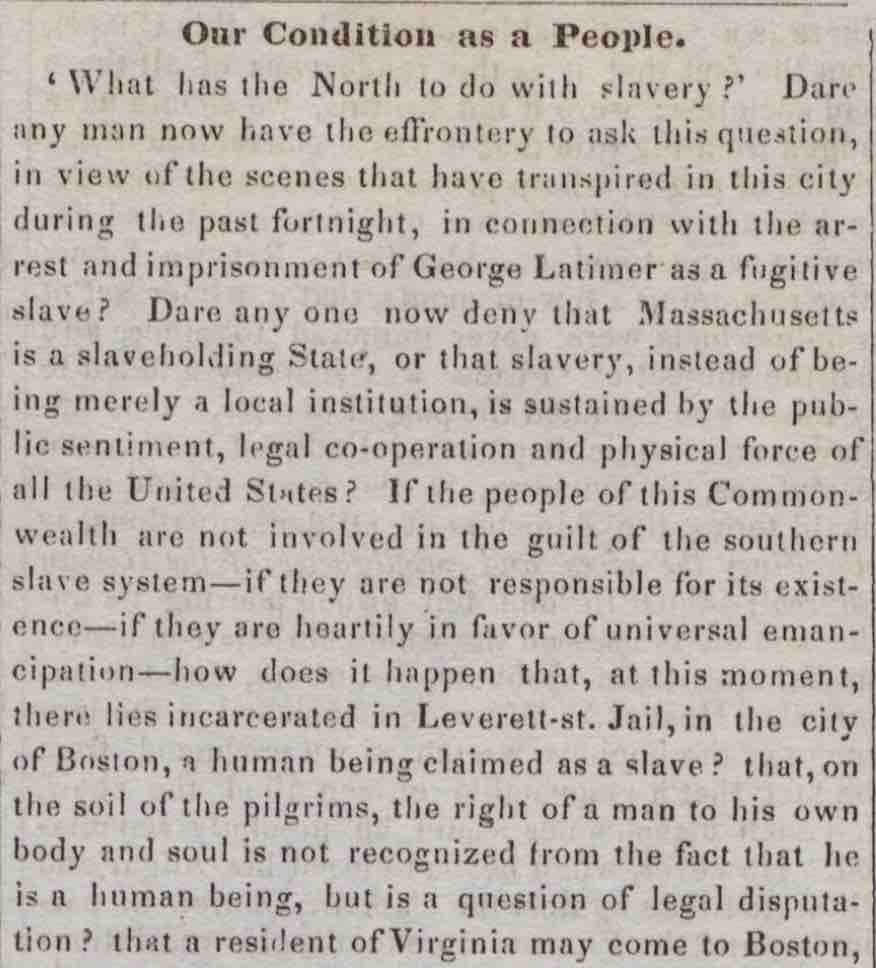

In 1842 antislavery people in Massachusetts were facing this hard question: What do you do when your national government supports slavery, but your state does not? They felt increasingly frustrated with their failure to stop slavery from expanding throughout the South and West. But they hoped that maybe they could keep the Slave Power from clawing its way into Massachusetts. The Latimer case galvanized the movement.

“Thoughts that breathe and words that burn”

Abolitionists were ready for this moment, having spent a decade developing communication channels, funding sources, professional speakers, and coordinated messaging. The story of George and Rebecca Latimer presented to them a cause they could champion, with a compelling narrative: the enslaved husband and wife, expecting their first child, pulled off a daring escape from slavery, and sought refuge in Massachusetts, the birthplace of freedom.

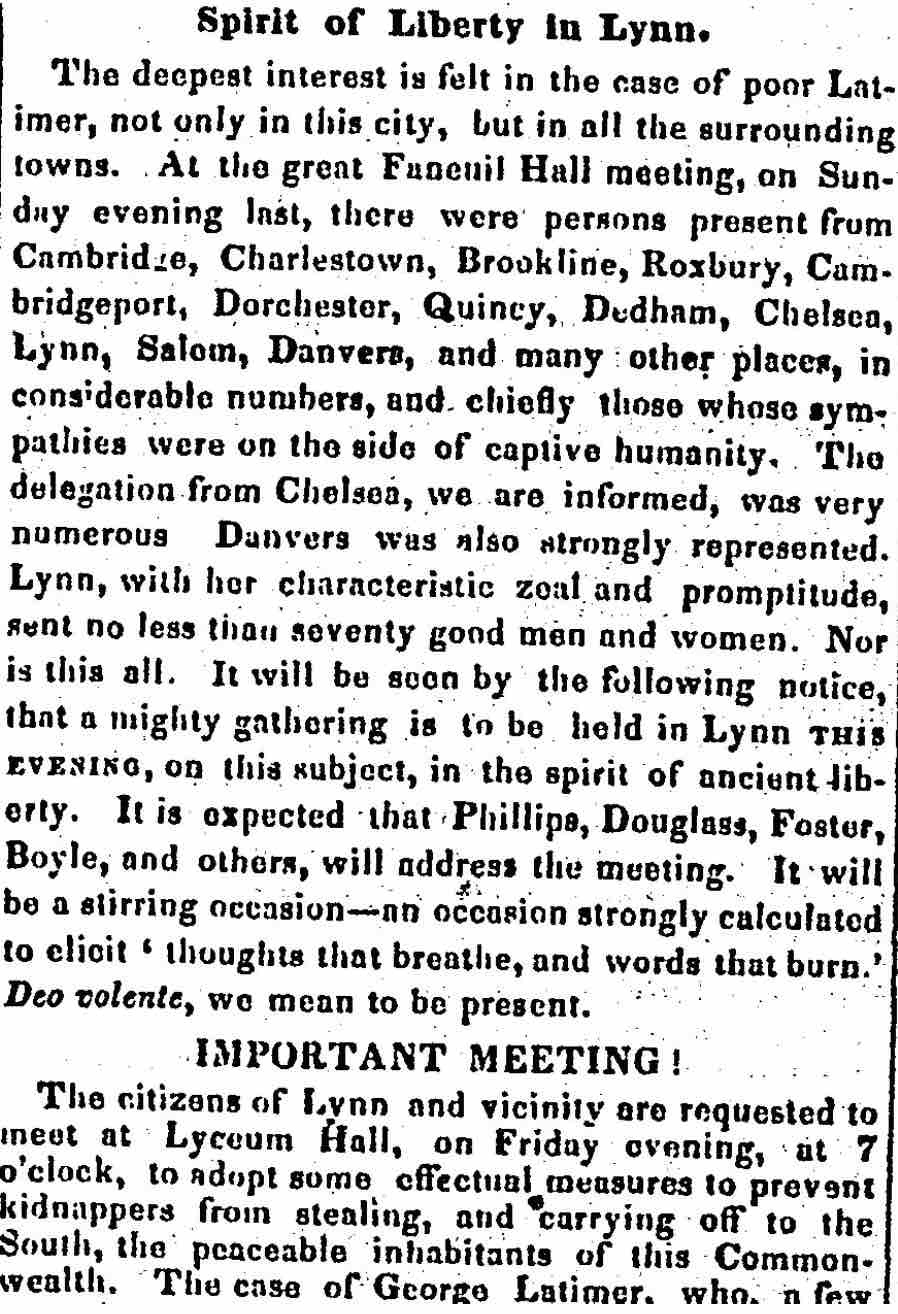

Across Eastern Massachusetts, the movement organized meetings to stir up support for George Latimer and his family. They held large gatherings at Faneuil Hall in Boston, and also in Lynn and Salem.

Some historians have suggested that George’s light skin added an implicit appeal to white Massachusetts residents, who may have empathized with him more because he looked like one of them. Various news reports emphasized this point.

“Slavehunting ground of the South”

George Latimer remained in Leverett Street jail for a month waiting for a trial judge to decide if Gray could remove him from the state. In the meantime local outrage was growing. Initially, abolitionists directed their anger at the individuals who worked for the city and who assisted the enslaver.

As the legal process dragged on, more protest focused on the broader dynamics that rendered Massachusetts complicit in slavery.

A young Frederick Douglass was one of the abolitionist lecturers speaking at large public meetings in 1842 on behalf of George Latimer. Speaking in New Bedford MA, Douglass pointed out how Latimer’s case made it clear that the Slave Power was at work here in Massachusetts. “We need not point to the sugar fields of Louisiana, or to the rice swamps of Alabama, for the bloody deeds of this soul-crushing system, but to the city of the pilgrims.”

Douglass and Latimer had much in common: both in their twenties, recently escaped from slavery in the upper South, newly married and beginning their families. Douglass moved with his family to Lynn, Massachusetts in 1841 when he began working as an abolitionist lecturer. Douglass shared that “I can sympathize with George Latimer, having myself been cast into a miserable jail on suspicion of my intending to do what he is said to have done, viz appropriating my own body to my use.”

Latimer’s release

In the days leading up to Latimer’s expected trial on November 21, the public outrage in Boston and eastern Massachusetts rose to a fever pitch, as Latimer’s legal prospects looked bleak. Yet both sides of the legal case realized that there was no way both Latimer and Gray would leave the state alive. Bostonians circulated a petition calling on the Suffolk County sheriff to release Latimer and to fire the jailer for abuse of power.

The following statement from the Boston Bee in 1842 described the final hours of negotiations over releasing Latimer. In short, the Black community in Boston paid Latimer’s enslaver to free him.

The early part of this week, two petitions were gotten up and signed by many abolitionists, requesting Sheriff Eveleth to order [the jailer] Cooledge to discharge Latimer from the jail, and containing several threats to cause C[ooledge]'s removal from office for his abuse of power. This alarmed Cooledge, and on Wednesday evening, he notified Gray that he could not act as his agent any longer, and frankly states his reasons, viz: the prejudice these abolitionists were creating against him. Of this step the latter party must have been aware, for on that evening, [Latimer’s attorney] Sewall called at the jail and directed Latimer how to act, should Gray attempt to take him into his own custody—to scream and raise an outcry, and then the negroes would rescue him. Fifteen or twenty negroes, too, watched the jail thro' the night of Wednesday, to prevent Gray from removing his property. On Thursday morning, the counsel for the negroes in the riot case in the Municipal Court obtained a writ of habeas corpus to have L[atimer] brought to the Court as a witness for the defence. On that day [November 17], an agreement was negotiated between a negro and Cooledge, for the purchase of the slave, and $800 was fixed as the price.

This was refused by the negro, who offered $650 for him, and upon [white abolitionist] Dr. Bowditch agreeing to pay that sum for George. Gray accepted it, and the parties were to meet at the jail office at 7 o'clock, to adjust the business. The hour came and brought the parties, but Dr. Bowditch stated that he had seen an order of the Sheriff directing Cooledge to discharge Latimer at 12 o'clock on Friday, and as Gray could not find a place strong enough to keep him from the negroes till the day of the hearing—and as he would of necessity be rescued, he should not pay any thing for him; and thus backed out of his contract, and boasted on that evening to a friend of ours, that he had failed to fulfill his agreement. A negro minister, however, offered Austin $400 for Latimer, which was accepted; and at 10 o'clock on Thursday evening, the money was paid, and the slave was made a free man.

George Latimer never forgot the kindness of the Black community who sustained his family, especially the Black minister who ultimately enabled him to live as a free man. Fifty years later, he said “I recall with gratitude the generous act of Rev. Dr. Caldwell, of the Tremont Temple Baptist Society, who raised the money with which I was redeemed.”

Up next

The story of George and Rebecca Latimer did not end there. The Latimer cause continued, and left a lasting impact on personal liberty laws in Massachusetts and other free states. In Part Two, I’ll describe the statewide campaign in which 66,000 Massachusetts residents signed a petition in George Latimer’s name, resulting in the state passing the 1843 Personal Liberty Law, also called the Latimer Law. And I’ll tell of the Latimer family and their lives in freedom.

Selected references

Cools, Amy M. 2016. “Frederick Douglass Lynn Sites, Part 2: Historical Society & Hutchinson Scrapbook.” Ordinary Philosophy blog. https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/tag/tremont-temple/

Davis, Asa J. 1995. “The George Latimer case.” from Blueprint for Change: The Life and Times of Lewis H. Latimer. https://edison.rutgers.edu/resources/latimer

Gac, Scott. 2015. “Slave or Free? White or Black? The Representation of George Latimer.” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 73–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24718203

Grodzins, Dean. 2015. “Constitution or No Constitution, Law or No Law: The Boston Vigilance Committees 1841-1861” in the book Massachusetts and the Civil War: The Commonwealth and National Disunion (pp.47-73). University of Massachusetts Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308171672_Constitution_or_No_Constitution_Law_or_No_Law_The_Boston_Vigilance_Committees_1841-1861

“Fugitive Slaves in Boston”. Massachusetts Legislature House reports No. 41. 1843. https://primaryresearch.org/qfugitive-slaves-in-massachusettsq/

Law Reporter. “An Article on the Latimer Case.” March 1843. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llst/067/067.pdf

National Park Service. “Faneuil Hall, the Underground Railroad, and the Boston Vigilance Committees.” https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/faneuil-hall-and-boston-vigilance-committees.htm

This was great, Chris! I learned so much about George Latimer's story and the legal maneuvering that took place. Thank you! I'm looking forward to part 2.